A Vanishing Land: Coastal Erosion In Canada’s Arctic

A Vanishing Land:

Canada’s Arctic feels impact of climate change as coastline disappears into the sea

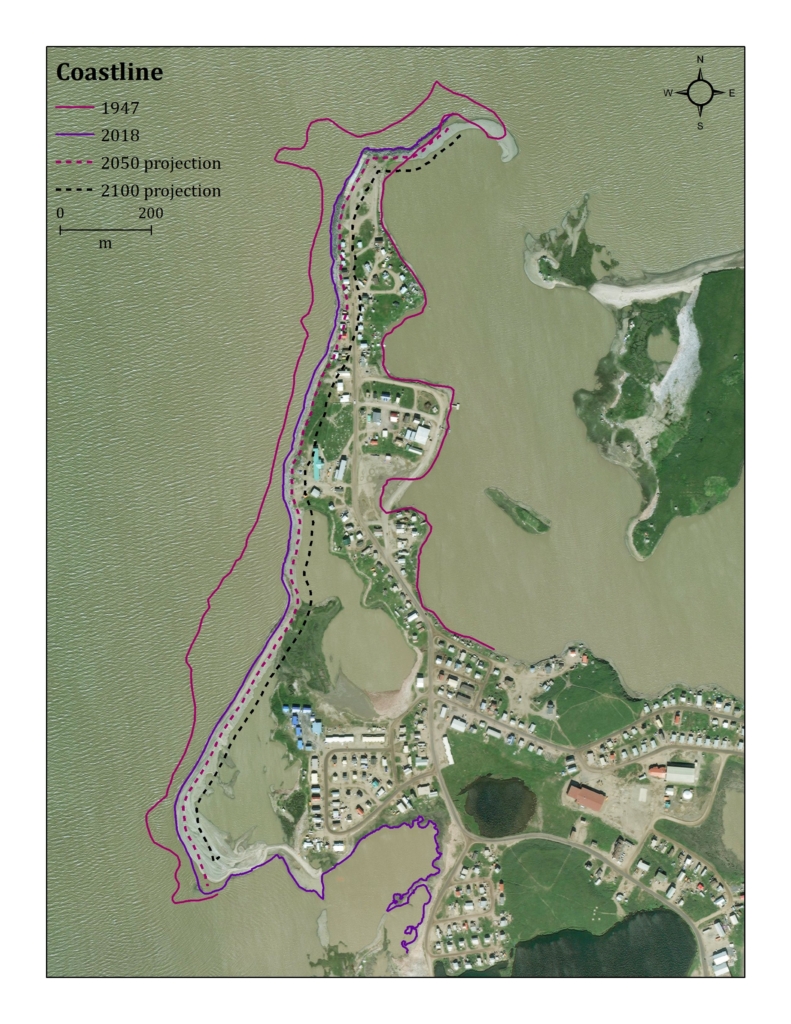

When a big storm hit Tuktoyaktuk on August 4, Beaufort Drive – the community’s main drag – was bustling with activity late into the night. Everyone’s eyes were on the Point, the north end of Tuktoyaktuk Peninsula that has made national news several times over the last couple of years as a place heavily impacted by climate and change and progressing shore erosion.

As the ocean battered the shoreline right below the foundation of their houses, homeowners on the windward side of the Point puttered around, checking on their properties and moving their snowmobiles and trucks out of harm’s way. “I won’t be getting much sleep tonight” said Noella Cockney, one of the residents of the Point, as she watched chunks of her driveway disappear into a growing undercut beside her porch.

It was just two years ago that Canada celebrated the opening of its first road to the Arctic Ocean, with a 137-kilometre highway that starts in Inuvik and ends in Tuktoyaktuk. The road has been a boon to the Inuvialuit community of 950 people, which has seen a massive influx of tourists eager to experience life on the country’s Northern coast. But by the end of the century, there may not be much of a community left to visit.

According to a report published by the Geological Survey of Canada, the Beaufort Sea coastal region is expected to experience the largest projected relative sea level rise of Canada’s North coast. By the end of the century water levels in the Beaufort are expected to rise by between 50 to 75 centimetres. Locally, the amount of water level change is affected by the global sea level, as well as vertical land motion. In the Canadian Arctic this land motion is primarily caused by a process called glacial isostatic adjustment – a delayed response to the surface decompressing after retreat of the continental ice sheets at the end of the last ice age.

As a result of that process, the areas that were compressed by the ice cover tend lift up, while the areas formerly located along the edge of the ice subside. Because of this process, Tuktoyaktuk is not only facing a threat from the rising water levels; the Beaufort Sea’s coastline around Tuktoyaktuk is also sinking by about 2.5 millimetres a year (20 centimetres over 80 years). These estimates refer to the movement of bedrock deep below the surface and do not account for additional land subsidence caused by factors like permafrost thaw.

I started to photograph the impact of climate change on the coastal landscape in the Mackenzie region in 2017. Despite having done a solid amount of research on the topic, I was not prepared to witness the scale of the damage. There are some striking examples of extreme erosion along the Beaufort coast that illustrate well how devastating the impact of global warming on the Arctic actually is.

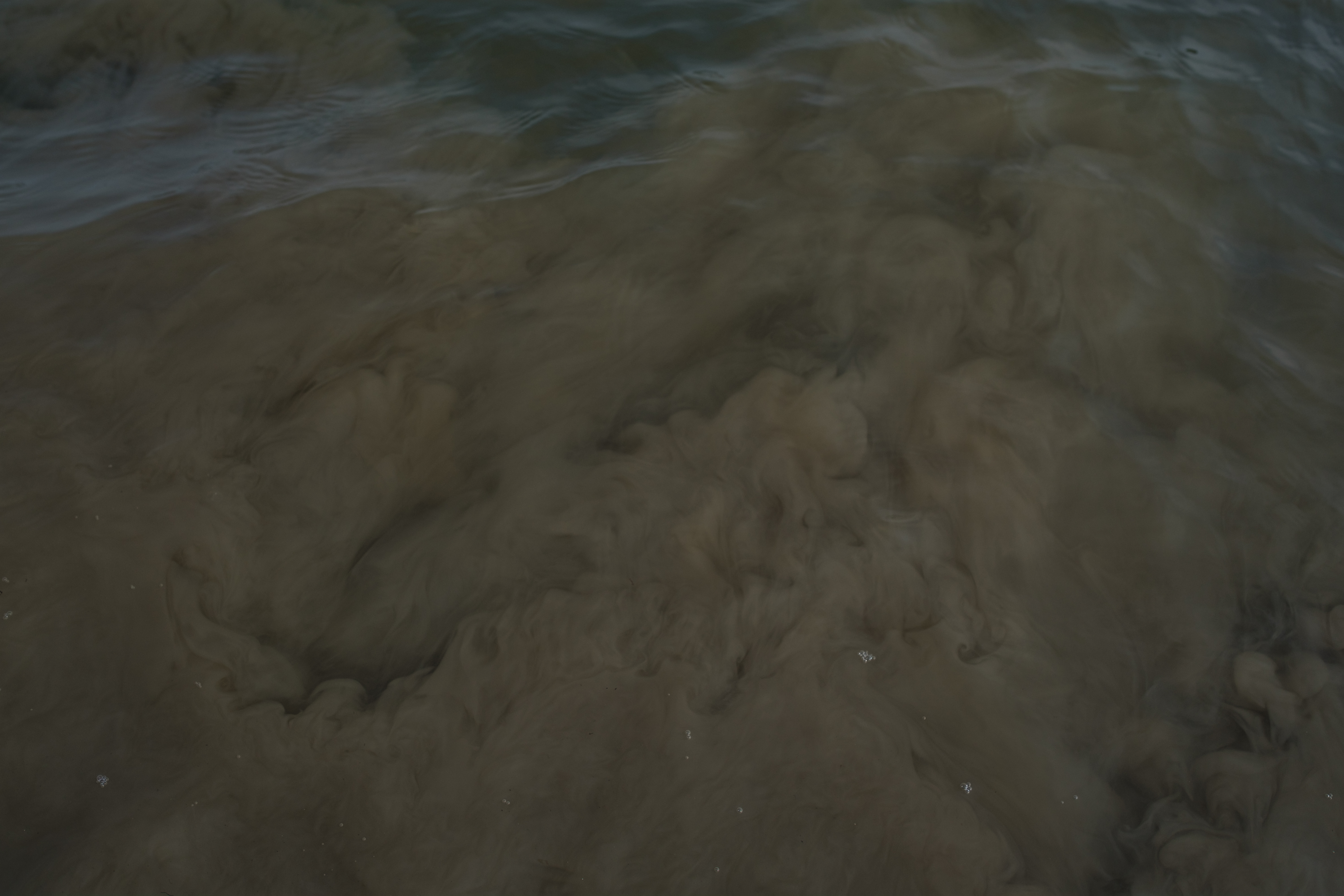

In August 2018 I spent six days in a research camp on Pelly Island, one of the fastest eroding places in this part of the world. Some sections of the island recede as much as 30 metres a year. In places like Pelly you are surrounded by the sounds of dripping and splotching as the exposed permafrost thaws away – you can smell it. You have to watch where you put your feet because there are deep crevasses in the tundra where the undercut blocks are beginning to separate from the island.

One of the biggest challenges of telling this story is trying to convey that the coastline is basically made up of frozen mud up. The cliffs in my photographs are not rock. The ground beneath our feet is frozen silty clay and organic matter – and the only thing holding it all together is ice. In Tuktoyaktuk the ground is about 90 per cent ice. You can often see very significant changes in the landscape unfold over weeks, or even days. That’s why this environment is so incredibly fragile and prone to erosion.

One of the biggest contributing factors to the accelerated rate of erosion is the increasingly shorter ice season. The lack of protection leaves the shore exposed to wind and waves for a longer period of time. According to the recently published report from W.F. Baird & Associates Coastal Engineers, the open water season on the Beaufort Sea around Tuktoyaktuk has increased from approximately 95 days to 110 days since 1975.

It is projected that it will further increase by another two months by 2060, and by three to four months by 2100. Loss of sea ice opens more water surface for the prevailing winds to create bigger waves. That, combined with rising sea level, is expected to bring increasingly higher storm surge, which will continue to devastate the shoreline and man-made infrastructure.

At least four households on the far end of the Tuktoyaktuk’s Point are now in immediate danger of being undercut by the ocean and are awaiting relocation further inland. When I photographed Noella last summer, she hoped that the new boulders added to the existing reinforcement behind her house a couple of years ago could buy her a few more years at the current location.

But the reinforced shoreline has since been breached and she is now out of time. Her home, built by her father, may turn out to be difficult to move, especially with the shoreline creeping up closer with every stormy day, making for unsteady ground for the heavy equipment to work on.

Will Tuktoyaktuk be the first community in Canada that will have to fully relocate due to climate change? You don’t have to look far to see how incredibly costly and complicated it may be – Alaskan villages of Newtok and Kivalina are facing imminent relocation due to flooding and coastal erosion, and are struggling with issues like lack of sufficient funding and infrastructure in the process.

One of the possible options that are under consideration is beach nourishment – essentially the creation of artificial beaches with material sourced at another location to protect the shore. The solution is costly and will not be attainable without outside funding. Depending on where the beach material would be sourced, the estimated cost of the project ranges between $26 million and $72 million.

There is no consensus in the community regarding possible relocation. It’ has been determined that based on the extent of the planning and research required for such a move, not to mention the need for agreement among the community members, it is not a decision that will be made any time soon. In the meantime, currently proposed remediation strategies are meant to buy Tuktoyaktuk more time so the community can make well informed choices about its future.

Pelly Island, one of my most photographed sites for this project, is expected to disappear within the next 50 years. If you don’t live in the Arctic, you may think that this is not your problem. But we are all standing on the edge of a crumbling cliff.

So sad, no words to express this loss.

amazing article. thank you for the jaw-dropping pics. perhaps you would like to contribute pictures to the joint NOAA/ECCC climate bulletin: https://www.canada.ca/en/environment-climate-change/services/climate-change/science-research-data/climate-trends-variability/quarterly-bulletins.html

please let me know.