British Columbia’s Forgotten Opioid Crisis

British Columbia’s Forgotten Opioid Crisis

Five years into BC’s overdose emergency

more families are struggling than ever

Story by Sarah Berman/photos by Jackie Dives

Glenn Young was in treatment for opioid addiction when COVID-19 lockdown first hit in March 2020. His mother Pam Young says his plan at the time was to stay in treatment for a full year, and then transition into working in the recovery sector. “He wanted to do some kind of outreach and, you know, get involved in helping guys who are dealing with addiction,” she said. “He was really excited about it.”

At 32 years old Glenn was a father to four daughters and engaged to marry his partner Dana Tough. Though he had made it past 30 days sober—a minimum requirement for family visits at the Lower Mainland facility he attended—it was COVID-19 restrictions that had prevented him from seeing his kids that spring.

Glenn struggled with the added separation, his mother said, which was weighing on him when he abruptly left treatment and relapsed last summer. Glenn Young became one of 185 people in British Columbia who died of an overdose in June 2020—the most drug overdoses the province has ever recorded in a single month.

As British Columbia tries to contain the spread of COVID-19, its failure to get a longstanding health crisis under control looms large. It has now been five years since the province first declared a public health emergency on April 14, 2016 due to the rising death toll of the opioid crisis. According to B.C.’s coroner, 6,853 people have died of drug poisoning since then.

In addition to struggles related to inadequate housing, job loss, gaps in social services, and an increasingly toxic drug supply made worse by border closures, the isolation and the mental health challenges that have arisen during the pandemic have contributed to a worrying rise in deaths in 2020 and the early months of 2021. In the past five years deaths have surged upwards every year except 2019. February 2021, the most recent data available, was the 11th consecutive month that recorded more than 100 toxic drug deaths. In total, 1,716 people died due to illicit drugs in 2020, a 74-per-cent increase in deaths since 2019.

The provincial government has responded to these intersecting emergencies by expanding the availability of overdose-reversing naloxone, supporting safe consumption sites across the province, and allowing some doctors and nurses to prescribe medical alternatives to street opioids. The City of Vancouver has also taken steps to apply for a federal exemption that would allow for the decriminalization of personal use for all drugs.

Drug user advocates say the “safe supply” program announced last year is only reaching a narrow segment of the province’s users so far. “The program has really stalled,” Crackdown podcast host Garth Mullins told CBC last month. “I know lots and lots of people who have been denied access to this program.” B.C.’s addictions and mental health minister said the number of people accessing safe hydromorphone rose to 3,329 last year. But that number pales in comparison to the estimated 77,000 British Columbians currently diagnosed with an opioid use disorder.

Bruce Alexander, a Simon Fraser University researcher who studies underlying causes of addiction, sees a connection between the rise in drug use disorders and our increasingly fragmented communities. He says harm reduction efforts are important and effective to a degree, but can only do so much in a society that marginalizes an underclass of drug users. Alexander advocates for additional big picture solutions that address inequality and social identity. “I think the answer really is, in a way, obvious. We have to take care of people,” he said.

In the meantime, more B.C. families have been directly impacted by the toxic drug crisis than ever before. According to an Insights West survey released in September 2020, 31 percent of British Columbians have someone in their immediate family or friends who is either struggling with addiction or has died from an overdose. For perspective, the survey found only 10 percent of respondents knew someone who had COVID-19 or had died from it.

Beginning in 2020 photographer Jackie Dives set out to spend time with families grieving the loss of loved ones like Glenn Young. These are their stories.

“Right after Robert died and we got back to B.C. there was all this talk about COVID. Every channel was COVID this and COVID that. Three people had died and it was this big thing. I lost it on the couch… 175 people died [from overdoses] last month, and the whole world’s talking about three people.”

“He had a high paying, full time job. He was a functional drug user and no one but his family knew. And that’s where the stigma comes in. He always used alone because he was always scared of people finding out.”

“He changed his life around after he got out of prison. He wanted to quit drugs, and was seeing a drug counsellor. Then Covid came around and the lack of community and the extra toxic drugs was a terrible combination. There isn’t enough help out there for people.”

“ People need support. The way that we’ve lost our kids, it’s just a double-edged sword. We’ve already gone through their addictions and tried to help them, and then they die in the end.”

“I loved her more than anything. I have her old diaries full of to-do lists. Ten years of to-do lists. Things like get a passport, get her art together and have a show, all these things that never happened.”

“I’d love to see him in his 30’s finding himself. Because, myself, it’s been a hard 30’s but really good. I’m trans and non binary, and [he died] before [I was] transitioning and before an autism diagnosis. I think of that person I was when he knew me and I don’t even know who that person was. I want him to see me now, and see what he would be like now.”

“We always wondered. We always asked ourselves what happened to her? Why is she suffering from this pain she has to escape from? We didn’t get it… She wouldn’t tell. We didn’t know until after her death and we found the journals.”

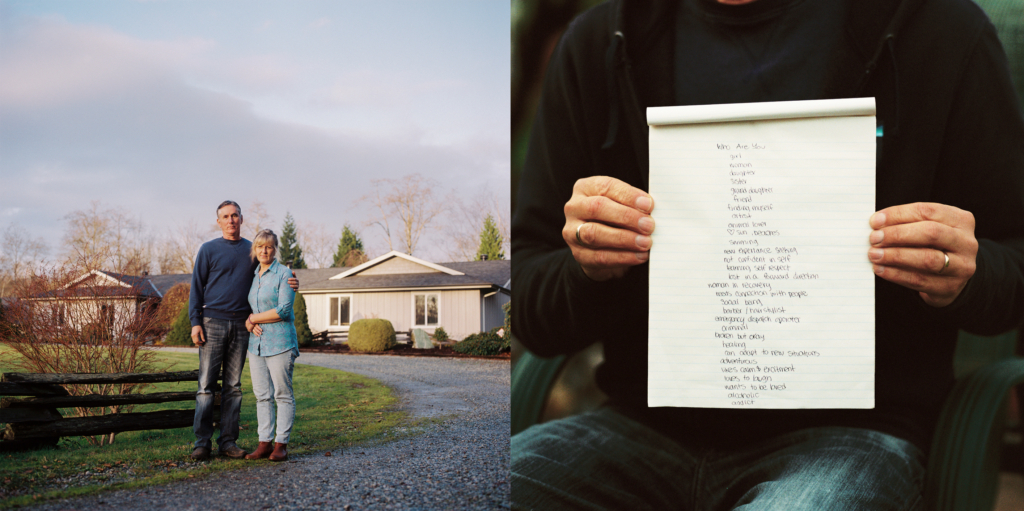

Right: Stuart Bedard holds a page of his daughter Renée’s writing. Over four pages Renée listed her many identities, as a daughter and sister and a woman in recovery.

“I phoned every facility from Vancouver, the Island, everywhere and they’re like, ‘No, sorry, we’re not taking anybody because of COVID and we don’t know where they’ve been…’ The waiting lists are ridiculous. There’s waiting lists without COVID. You add COVID into that and it’s just escalated 100 percent.”

Right: Mitchell and Lauren Radu wanted to be photographed in front of this mural, which was painted in their brother Morgan’s honour.

“Becoming a mother myself made me think of his loss in a whole new way. When she’s old enough I do want to tell [my daughter] the circumstances around his death. And I hope she can be a leader to her peers to spread awareness and not go down that path.”

[…] “British Columbia’s Forgotten Opioid Crisis” — True North Journal […]

[…] “British Columbia’s Forgotten Opioid Crisis” — True North Journal […]